LM 22.2 The gravitational field Collection

Tags | |

UUID | 1e99eda1-f145-11e9-8682-bc764e2038f2 |

22.2 The gravitational field by Benjamin Crowell, Light and Matter licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

22.2 The gravitational field

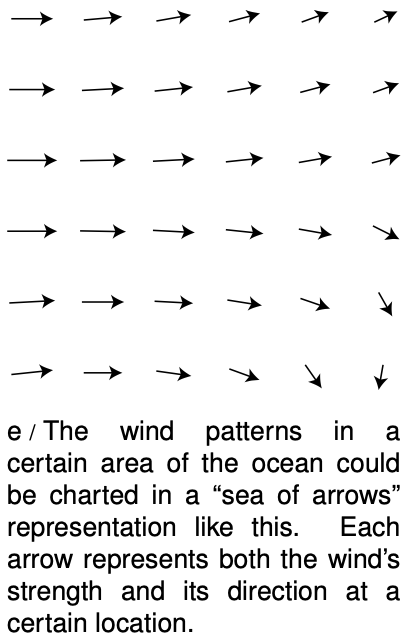

Given that fields of force are real, how do we define, measure, and calculate them? A fruitful metaphor will be the wind patterns experienced by a sailing ship. Wherever the ship goes, it will feel a certain amount of force from the wind, and that force will be in a certain direction. The weather is ever-changing, of course, but for now let's just imagine steady wind patterns. Definitions in physics are operational, i.e., they describe how to measure the thing being defined. The ship's captain can measure the wind's “field of force” by going to the location of interest and determining both the direction of the wind and the strength with which it is blowing. Charting all these measurements on a map leads to a depiction of the field of wind force like the one shown in the figure. This is known as the “sea of arrows” method of visualizing a field.

Given that fields of force are real, how do we define, measure, and calculate them? A fruitful metaphor will be the wind patterns experienced by a sailing ship. Wherever the ship goes, it will feel a certain amount of force from the wind, and that force will be in a certain direction. The weather is ever-changing, of course, but for now let's just imagine steady wind patterns. Definitions in physics are operational, i.e., they describe how to measure the thing being defined. The ship's captain can measure the wind's “field of force” by going to the location of interest and determining both the direction of the wind and the strength with which it is blowing. Charting all these measurements on a map leads to a depiction of the field of wind force like the one shown in the figure. This is known as the “sea of arrows” method of visualizing a field.

Now let's see how these concepts are applied to the fundamental force fields of the universe. We'll start with the gravitational field, which is the easiest to understand. As with the wind patterns, we'll start by imagining gravity as a static field, even though the existence of the tides proves that there are continual changes in the gravity field in our region of space. Defining the direction of the gravitational field is easy enough: we simply go to the location of interest and measure the direction of the gravitational force on an object, such as a weight tied to the end of a string.

But how should we define the strength of the gravitational field? Gravitational forces are weaker on the moon than on the earth, but we cannot specify the strength of gravity simply by giving a certain number of newtons. The number of newtons of gravitational force depends not just on the strength of the local gravitational field but also on the mass of the object on which we're testing gravity, our “test mass.” A boulder on the moon feels a stronger gravitational force than a pebble on the earth. We can get around this problem by defining the strength of the gravitational field as the force acting on an object, divided by the object's mass.

definition of the gravitational field: The gravitational field vector, g, at any location in space is found by placing a test mass mt at that point. The field vector is then given by , where F is the gravitational force on the test mass.

The magnitude of the gravitational field near the surface of the earth is about 9.8 N/kg, and it's no coincidence that this number looks familiar, or that the symbol g is the same as the one for gravitational acceleration. The force of gravity on a test mass will equal mtg, where g is the gravitational acceleration. Dividing by mt simply gives the gravitational acceleration. Why define a new name and new units for the same old quantity? The main reason is that it prepares us with the right approach for defining other fields.

The most subtle point about all this is that the gravitational field tells us about what forces would be exerted on a test mass by the earth, sun, moon, and the rest of the universe, if we inserted a test mass at the point in question. The field still exists at all the places where we didn't measure it.

Example 1: Gravitational field of the earth

⇒ What is the magnitude of the earth's gravitational field, in terms of its mass, M, and the distance r from its center?

⇒ Substituting |F|=GMmt/r2 into the definition of the gravitational field, we find |g|=GM/r2. This expression could be used for the field of any spherically symmetric mass distribution, since the equation we assumed for the gravitational force would apply in any such case.

Sources and sinks

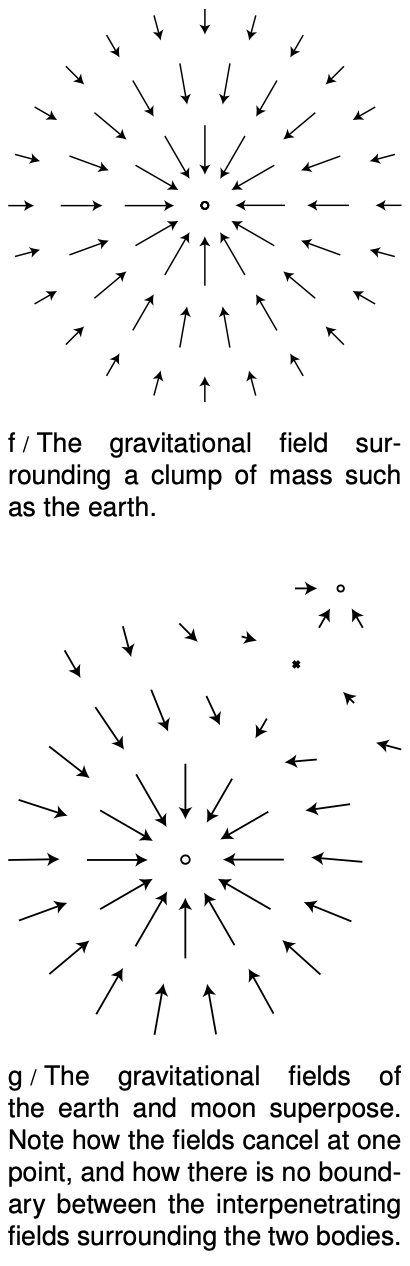

If we make a sea-of-arrows picture of the gravitational fields surrounding the earth,

f, the result is evocative of water going down a drain. For this reason, anything that creates an inward-pointing field around itself is called a sink. The earth is a gravitational sink. The term “source” can refer specifically to things that make outward fields, or it can be used as a more general term for both “outies” and “innies.” However confusing the terminology, we know that gravitational fields are only attractive, so we will never find a region of space with an outward-pointing field pattern.

If we make a sea-of-arrows picture of the gravitational fields surrounding the earth,

f, the result is evocative of water going down a drain. For this reason, anything that creates an inward-pointing field around itself is called a sink. The earth is a gravitational sink. The term “source” can refer specifically to things that make outward fields, or it can be used as a more general term for both “outies” and “innies.” However confusing the terminology, we know that gravitational fields are only attractive, so we will never find a region of space with an outward-pointing field pattern.

Knowledge of the field is interchangeable with knowledge of its sources (at least in the case of a static, unchanging field). If aliens saw the earth's gravitational field pattern they could immediately infer the existence of the planet, and conversely if they knew the mass of the earth they could predict its influence on the surrounding gravitational field.

Superposition of fields

Example 2: Reduction in gravity on Io due to Jupiter's gravity

⇒ The average gravitational field on Jupiter's moon Io is 1.81 N/kg. By how much is this reduced when Jupiter is directly overhead? Io's orbit has a radius of 4.22×108 m, and Jupiter's mass is 1.899×1027 kg.

⇒ By the shell theorem, we can treat the Jupiter as if its mass was all concentrated at its center, and likewise for Io. If we visit Io and land at the point where Jupiter is overhead, we are on the same line as these two centers, so the whole problem can be treated one-dimensionally, and vector addition is just like scalar addition. Let's use positive numbers for downward fields (toward the center of Io) and negative for upward ones. Plugging the appropriate data into the expression derived in example 1, we find that the Jupiter's contribution to the field is -0.71 N/kg. Superposition says that we can find the actual gravitational field by adding up the fields created by Io and Jupiter: 1.81 - 0.71 N/kg = 1.1 N/kg. You might think that this reduction would create some spectacular effects, and make Io an exciting tourist destination. Actually you would not detect any difference if you flew from one side of Io to the other. This is because your body and Io both experience Jupiter's gravity, so you follow the same orbital curve through the space around Jupiter.

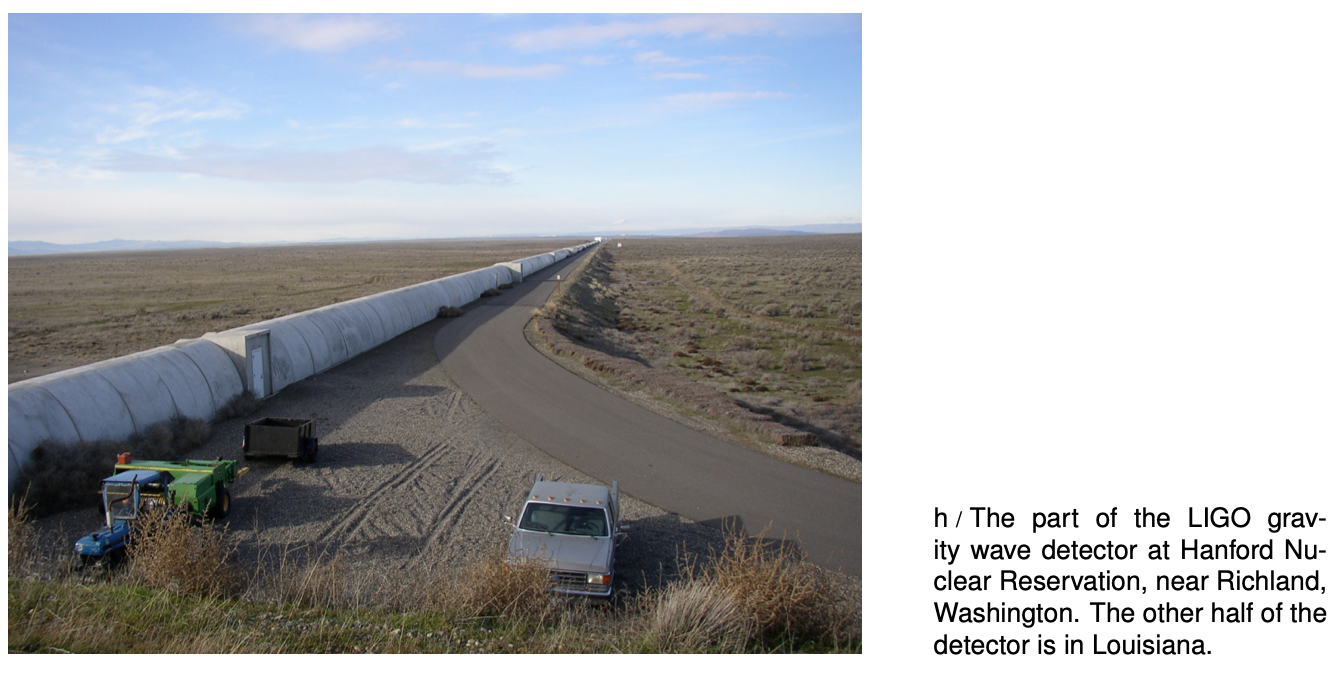

Gravitational waves

Acceleration Due to Gravity in the Solar System:

- g(Sun) = 274 m/s²

- g(Mercury) = 3.7 m/s²

- g(Venus) = 8.87 m/s²

- g(Moon) = 1.62 m/s²

- g(Earth) = 9.80665 m/s²

- g(Mars) = 3.71 m/s²

- g(Jupiter) = 24.79 m/s²

- g(Saturn) = 10.44 m/s²

- g(Uranus) = 8.87 m/s²

- g(Neptune) = 11.15 m/s²

- g(Pluto) = 0.62 m/s²

22.2 The gravitational field by Benjamin Crowell, Light and Matter licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

Calculators and Collections

Equations

- Gravitational Field Vector vCollections Use Equation

- Force of Gravity MichaelBartmess Use Equation

- Acceleration Due to Gravity KurtHeckman Use Equation

Data Items

- g (acceleration due to gravity at sea level) MichaelBartmess Use Data Item

- Comments

- Attachments

- Stats

No comments |