3.6 Algebraic Results for Constant Acceleration by Benjamin Crowell, Light and Matter licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

3.6 Algebraic results for constant acceleration

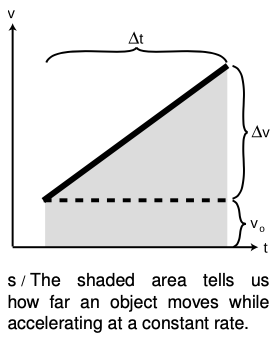

Although the area-under-the-curve technique can be applied to any graph, no matter how complicated, it may be laborious to carry out, and if fractions of rectangles must be estimated the result will only be approximate. In the special case of motion with constant acceleration, it is possible to find a convenient shortcut which produces exact results. When the acceleration is constant, the v - t graph is a straight line, as shown in the figure. The area under the curve can be divided into a triangle plus a rectangle, both of whose areas can be calculated exactly: `A=b⋅h` for a rectangle and `A=1/2 b*h` for a triangle. The height of the rectangle is the initial velocity, `v_o`, and the height of the triangle is the change in velocity from beginning to end `Deltav`. The object's `Deltax` is therefore given by the equation `Deltax=v_o Deltat +1/2 (Deltav)/(Deltat) * Deltat^2` . This can be simplified a little by using the definition of acceleration, `a`= `Deltav`/`Deltat`, to eliminate `Deltav`, giving

`Delta x = v_0*Delta t + 1/2 a *Delta t^2`. [motion with constant acceleration]

Since this is a second-order polynomial in `Deltat`, the graph of`Deltax` versus `Deltat` is a parabola, and the same is true of a graph of `x` versus `t` the two graphs differ only by shifting along the two axes. Although I have derived the equation using a figure that shows a positive `v_o`, positive `a`, and so on, it still turns out to be true regardless of what plus and minus signs are involved.

Another useful equation can be derived if one wants to relate the change in velocity to the distance traveled. This is useful, for instance, for finding the distance needed by a car to come to a stop. For simplicity, we start by deriving the equation for the special case of `v_o`=`0`, in which the final velocity `v_f` is a synonym for`Deltav`. Since velocity and distance are the variables of interest, not time, we take the equation `Deltax = 1/2 a Deltat^2` and use `Deltat = (Deltav)/a` to eliminate`Deltat`. This gives `Deltax = (Deltav)^2/(2a)`, which can be rewritten as

Another useful equation can be derived if one wants to relate the change in velocity to the distance traveled. This is useful, for instance, for finding the distance needed by a car to come to a stop. For simplicity, we start by deriving the equation for the special case of `v_o`=`0`, in which the final velocity `v_f` is a synonym for`Deltav`. Since velocity and distance are the variables of interest, not time, we take the equation `Deltax = 1/2 a Deltat^2` and use `Deltat = (Deltav)/a` to eliminate`Deltat`. This gives `Deltax = (Deltav)^2/(2a)`, which can be rewritten as

`v_f^2 = 2aDeltax` . [motions with constant acceleration, v0 = 0]

For the more general case where v0 ≠ 0, we skip the tedious algebra leading to the more general equation,

`v_f^2= v_0^2 + 2aDeltax` . Solved for `v_f = sqrt( v_0^2 + 2*a*Delta x)` [motion with constant acceleration]

To help get this all organized in your head, first let's categorize the variables as follows:

Variables that change during motion with constant acceleration:

`x,v, t`

Variable that doesn't change:

`a`

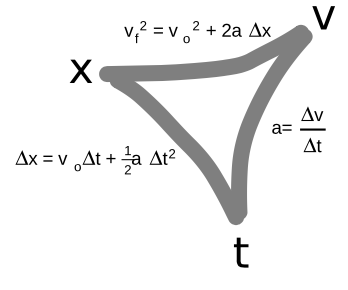

If you know one of the changing variables and want to find another, there is always an equation that relates those two:

The symmetry among the three variables is imperfect only because the equation relating `x` and `t` includes the initial velocity.

`Deltat = sqrt((2Deltax)/a)`

There are two main difficulties encountered by students in applying these equations:

- The equations apply only to motion with constant acceleration. You can't apply them if the acceleration is changing.

- Students are often unsure of which equation to use, or may cause themselves unnecessary work by taking the longer path around the triangle in the chart above. Organize your thoughts by listing the variables you are given, the ones you want to find, and the ones you aren't given and don't care about.

Example 7: Saving an old lady

⇒ You are trying to pull an old lady out of the way of an oncoming truck. You are able to give her an acceleration of 20m/`s^2`. Starting from rest, how much time is required in order to move her 2 m?

⇒ First we organize our thoughts:

Variables given: `Deltax,a,v_o`

Variables desired: `Deltat`

Irrelevant variables: `v_f`

Consulting the triangular chart above, the equation we need is clearly `Delta x = v_0*Delta t + 1/2 a *Delta t^2`, since it has the four variables of interest and omits the irrelevant one. Eliminating the `v_o` term and solving for `Deltat` gives `Deltat = sqrt((2Deltax)/a)`=0.4 s.

⇒ Solved problem: A stupid celebration — problem 15

⇒ Solved problem: Dropping a rock on Mars — problem 16

⇒ Solved problem: The Dodge Viper — problem 18

⇒ Solved problem: Half-way sped up — problem 22

Discussion Questions

A In chapter 1, I gave examples of correct and incorrect reasoning about proportionality, using questions about the scaling of area and volume. Try to translate the incorrect modes of reasoning shown there into mistakes about the following question: If the acceleration of gravity on Mars is 1/3 that on Earth, how many times longer does it take for a rock to drop the same distance on Mars?

B Check that the units make sense in the three equations derived in this section.

3.6 Algebraic Results for Constant Acceleration by Benjamin Crowell, Light and Matter licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.